Managing Heat Stress in Transition Cows: How X-Zelit Can Help Your Herd Succeed

As temperatures climb, so do the challenges dairy cows must confront, especially during the transition period. This critical window, spanning three weeks before and after calving, sets the stage for a cow’s future health, productivity, and fertility. Add heat stress to the picture, and you magnify potential risks.

Today, our industry has many tools in our toolbox that allow dairy producers to fine-tune their management and nutrition strategies to help transition cows remain healthy and productive, even during the hottest months of the year.

Why Heat Stress Hits Transition Cows Hard

Heat stress occurs when cows can’t dissipate enough body heat to maintain a normal core temperature. Once the Temperature-Humidity Index (THI) rises above 68, cows begin to experience stress. For transition cows, who are already managing major hormonal and metabolic shifts, this added pressure can lead to:

· Reduced dry matter intake (DMI)

· Compromised immune function

· Increased risk of subclinical and clinical hypocalcemia

· Increased risk of retained placentas and metritis, resulting in other metabolic diseases

· Elevated core body temperatures, which can lead to other health and productivity challenges

In short, it becomes a perfect storm of metabolic stress, occurring when cows need to perform at their best.

The Calcium Connection

Calcium might not be the first thing that comes to mind during a heatwave, but it’s something that’s also impacted. Cows require calcium for muscle contractions, immune responses, and milk production. During the transition period, calcium demand increases dramatically, just as pre-fresh DMI intake drops. Now add heat stress, additional feed intake reduction, and a weakened immune system with the normal physiological and metabolic challenges at calving – clearly, the transition cow has a lot to deal with!

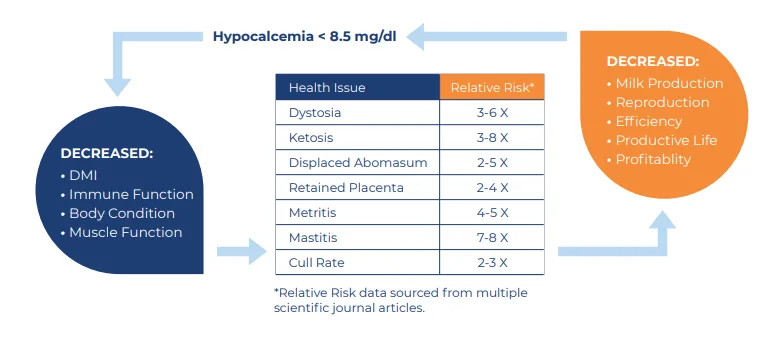

During these times of additional stress, the silent and costly issue of subclinical hypocalcemia, or low blood calcium without visible symptoms, can intensify. Subclinical hypocalcemia affects up to 40 to 50 percent of second-lactation and older cows. When combined with heat stress, the negative effects of this insidious problem become even more pronounced.

X-Zelit and New Casta Liquid: A Novel Approach to Calcium Management

X-Zelit and new Casta Liquid offer an innovative way to help reduce the stress associated with summer heat in both a dry (X-Zelit) and a liquid (Casta Liquid) form. These products work by inducing a mild hypophosphatemia through binding dietary phosphorus. This triggers bone calcium mobilization, significantly improving blood calcium levels during and after calving.

Why Is Proactively Managing Hypocalcemia Especially Helpful During Heat Stress?

– Helps Maintain Dry Matter Intake

X-Zelit and Casta Liquid allow more flexible pre-fresh diets because dietary K does not interfere with blood calcium response. This means more palatable forages like haylage and other small-grain forages can make their way back into the diet rather than having to rely heavily on straw. Through feeding more palatable forages, this helps maintain DMI through heat events and makes for a smoother transition from close-up to fresh diet.

– Supports DINCU and Stocking Density Management

X-Zelit and Casta Liquid are recommended for use 14 to 21 days in close-up (DINCU). Pre-fresh cows generate significant metabolic heat, so it’s critical to help control the heat load in the close-up period. By using these proven pre-fresh milk fever prevention strategies, you can also manage stocking density more effectively, maintaining lower pen populations that decrease excess body heat, support feed intake, and reduce stress from overcrowding.

– Promotes a Smooth Transition

More stable intakes through the transition period and less social and metabolic stress lead to greater metabolic stability. This leads to fewer veterinarian interventions, better transitions, and overall healthier fresh cows.

– Helps Maintain Stable Blood Calcium

X-Zelit and Casta Liquid are a novel pre-fresh hypocalcemia management strategy that robustly improves blood calcium by inducing a mild hypophosphatemia and triggering bone mobilization. This lowers the risk of both clinical and subclinical hypocalcemia and the metabolic disorders that follow.

Heat Stress Management is a Team Effort

While the diet is a powerful tool, it works best as part of a complete heat stress mitigation strategy. It’s critical to also provide:

· Proper ventilation and shade

· Fans and sprinkler systems

· Constant access to clean, cool water

· Consistent delivery of a properly mixed & stable TMR

Together, these strategies can significantly reduce the toll that heat stress takes on not only your transition cows, but also your entire herd.

Final Thoughts

Heat stress is more than just discomfort for cows. It impacts health, productivity, and your bottom line. Transition cows are especially vulnerable, so proactive planning is essential for lactation success.